SO HOW DOES IT WORK?

One of the most common questions we receive here at Lishtot is how does the sensor work? It never touches the water, so how can it determine anything regarding the quality of my drinking water. Below is a brief discussion of the science behind the sensor.

The phenomenon behind the all Lishtot detection systems is Triboelectric charging. There are several papers (for example) that show water is near the top of the table--the only thing more positive than water is air. Thus, for any material, water contacting/rubbing that material will lead to electron transfer to the non-water entity, such as a clean plastic cup. One group found that less clean water had a lower electric field on an associated plastic pipe than clean water did. In all of the previous work, two electrodes were used--one on the plastic tube and one in the water—which is a big difference from the Lishtot technology. As swirling water charges up the plastic cup, we can measure the electric field on the cup, without requir-ing two electrodes or any contact with the water in the cup. Thus, we measure electric fields around the cup, and the shape and strength of those fields give us information on the water and its contents. For an idea of some of Lishtot's patent material, please see the links below:

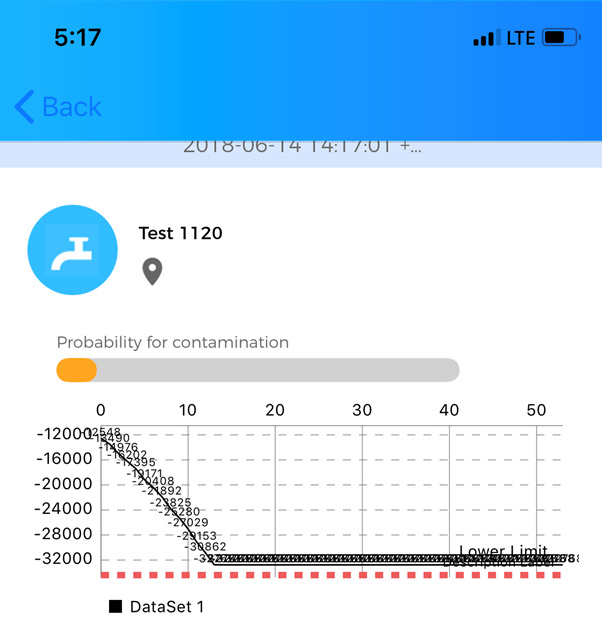

Our sensor is unique in that it has a single, uncharged electrode. There is no circuit, there are not two electrodes--just one, passive electrode. When you push the button you activate the system to measure the field strength around it, and as you move the device towards the cup, the uncharged electrode senses the electric field changes it is experiencing. The field around a cup with clean water is super-negative (due to the large transfer of electrons from water to the plastic cup through simple swirling); when the device ap-proaches, it experiences a massive negative field. The graph looks like a hockey stick that bottoms out due to the limits of the battery. We define a cutoff and a % of the graph that needs to be under this cut-off. So for example, I can set the cutoff at a certain number determined with clean water all over the world and that 10% of the graph must be under this number. If we reach this value for 10% or longer of the test, we get blue. Anything else is red. The three buttons have different cutoffs on them. All three buttons are programmable and all three have different cutoff values, from the least stringent (nature but-ton) to the most stringent (bottle button).

Here is a graph of water from the tap of a local student chemistry lab:

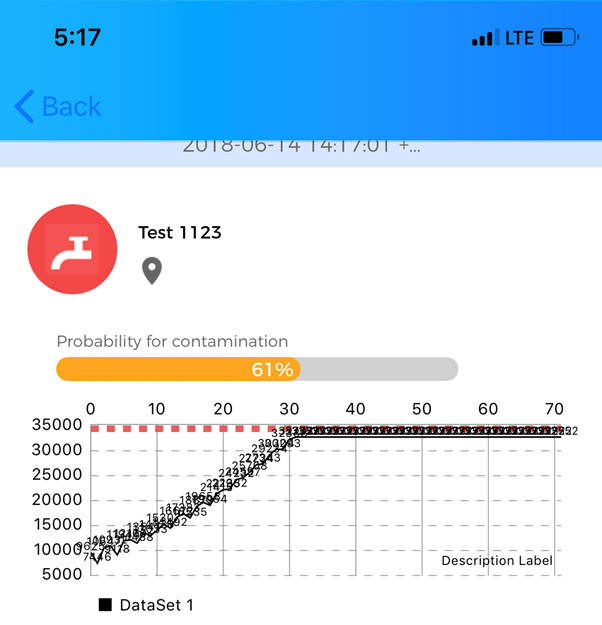

So how do contaminants change the signal? As we wrote above, water gives electrons to almost every other material. So if you have protein in the water, the water gives protein its electrons while it is still in another container (no mixing in the test cup ever---all mixing prior to testing). When you pour the pro-tein/water into a clean cup and swirl, fewer water electrons get to the wall of the cup and you get a much smaller signal. A lower signal means red. Heavy metals do not work by this mechanism as they cannot accept electrons, so we think they work by shielding the field in the cup and thus lowering the overall field felt by the device as it approaches the cup. Sensitivities have been shown to ppb and in some cases ppt. Ppm usually wipes out signal. Some real electron lovers like the Teflon chemicals can give positive signal as they not only gobble up the water electrons but also "steal" from the cup. See the next graph:

Glass and other materials give much less signal. Also a cup made of glass usually has residual of soap, etc. so you can't get an idea of actual water quality. Most normal plastics--PP, PS, PET, ETC.--work with the method. Use a clean, fresh cup for each test. Once you've charged up a cup, you can't use it again--it will give blue anyway.

This is just a brief explanation of the Lishtot detection technology. Feel free to contact me at alan@lishtot.com. I'll do my best to answer your questions.

Alan Joseph Bauer, Ph.D

Chief Scientist

Lishtot Detection, Ltd.